This week I was at a Public Speaking Competiton in memory  of Ian Gow the former MP for Eastbourne and Northern Ireland Secretary murdered by a bomb some 25 years ago. Ian was a vociferous opponent of the broadcasting of parliament so it was ironic he was to give the first televised speech in the House of Commons. A great piece of oratory, its well worth the 15 minutes or so to watch it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=La00bV3I4q8

of Ian Gow the former MP for Eastbourne and Northern Ireland Secretary murdered by a bomb some 25 years ago. Ian was a vociferous opponent of the broadcasting of parliament so it was ironic he was to give the first televised speech in the House of Commons. A great piece of oratory, its well worth the 15 minutes or so to watch it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=La00bV3I4q8

The MP for Eastbourne Caroline Ansell was inspired by Mr Gow and initiated this event for local schoolchildren aged 13-14. The topic they were given to speak on was ‘Democracy’ (an apposite topic in the light of the challenge to ‘our’ way of life posed by Da’ish) and the pupils from 5 schools had 10 minutes in groups of 3. The judging panel included Broadcaster and Journalist David Dimbleby also a local resident. I decided to attend on the basis you are never too old to learn from others not matter how young.

The performances were hugely impressive and reflected well on the UK’s oft maligned education system. Well reasoned arguments were put forward by articulate youngsters often with humour and passion. Of course there were the odd hiccup’s: one group who spoke without notes forget their lines; another group used stapled notes and got them mixed up; and when some groups used the lecterns they became a barrier between them and the 100 strong audience.

The 3 winners, from Gildredge House School, were well rehearsed, used small prompt cards (no lectern) and spoke with clarity, purpose and passion.

Here are my ten speech making recommendations (having heard Claire Carpenter, a speaking coach and the chair of judges, give her critique).

- Think: about how you dress for the occassion; to blend in or to stand out?

- Open: make a strong start; share the journey on how you came to be here.

- Heart: show passion with humility as well as humour, if you believe then the audience will find your conviction compelling.

- Pace: be constant, don’t go faster as you near the end.

- Pause: for key points by looking up at the audience.

- Knowledge: demonstrate by using stories and statistics to illuminate what you are saying; make the stories relevant to the audience.

- Intrigue: pose rhetorical questions (and let the silence hang).

- Notice: be aware of the audience; let them feel part of the speech.

- Implements: ensure props and prompts do not become barriers.

- Hold: your audience is likely to remember a maximum of three messages/points.

As someone who has delivered keynote speeches across 4 continents I am indebted to the training I received back in the 1980’s when I worked at Saudi International Bank. Each of the front line managers were sent away for a couple of days to work on presentation and speech making. Much of what I learned then has stuck, especially the need to use the ‘did you get that’ pause while looking up at the audience when making a key point.

Perhaps the greatest lesson was this, no matter what the technology or means of delivery: ‘Tell them what you are going to say, say it and then tell them what you said.’

Which brings me to the related item I’d like to raise.

‘A tool to make experts better’

Instead of watching TV I often spend some of my leisure time looking at TedTalks. Recently, thanks to a recommendation by Dr Dominique Poole-Avery of Arup, I viewed a thought provoking lecture ‘How do we heal medicine’ given by Dr Atul Gawande and seen by more than a million.

Author of The Checklist Manifesto, Dr Gawande charts the expenential growth of knowledge in medicine contrasting the experience of entering hospital in 1937 with that of today. Then, if your symptom didn’t fit one of the main areas of clinical expertise, your survival was questionable whereas today the problem is not too little but too much knowledge (of the tens of thousands of conditions a human can contract) and being able to pinpoint the symptom and prescribe the right medication or surgical procedure.

Then, autonomy and independence were the prized values. Today there is a recognition that we cannot know everything and everyone is a specialist with a piece of the care pathway but the constraint now is cost not knowledge.

He pointed out that there is a limited correlation between the cost of care and the effectiveness of the treatment. Having great components isn’t enough, it has to be about how it all comes together and used the anology of how pulling together the best parts of the best cars wouldn’t make the best car – it would be a piece of expensive junk!

The drive for cost management has meant health care has to become more process driven. In surgery people are very well trained with great technology but often it isn’t joined up with repeatable processes like aviation as an example.

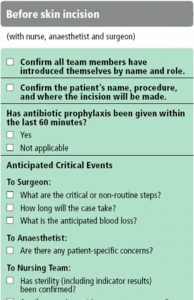

He spoke eloquently about the how the use of a 19 item 2 minute checklist (process – see alongside) helped to bring about a 47% reduction in surgical mortality rates in 8 hospitals across the globe during a World Health Organisation sponsored initiative. It was bigger than a drug!

He spoke eloquently about the how the use of a 19 item 2 minute checklist (process – see alongside) helped to bring about a 47% reduction in surgical mortality rates in 8 hospitals across the globe during a World Health Organisation sponsored initiative. It was bigger than a drug!

What I found compelling is the recognition that surgical team set up (and introductions) are just as important as anticipation of critical events.

The checklist forces people to confront the fact they are not a system and to work with humilty, discipline and teamwork.

Having visited Darfur as part of a WHO mission in 2010 and then Khartoum in 2013 to help Sudan’s Health Industry to look at what Knowledge Management might do for them I have seen the importance of checklists as a Knowledge Transfer tool.

My message to the young speech makers (and to all who read this), we can all learn from others no matter what age or profession. Dr Gawande’s TedTalk ticks most of the good speech boxes while also making some memorable points about the importance of a tool that has become a life saver and shows the power of Knowlege Management.

So what is a checklist? A tool or process that consolidates best knowledge and needs constant updating to reflect new experiences of practioners, organisations and communities.

And finally

The keen eyed among you with a gift for scrabble may have worked out that the ten observations above form ‘THINK HIPPO’.