A few month’s back during a Skype call with Dr Gada Kadoda a Professor at University of Khartoum she told me: ‘at last year’s KMCA Sudan many of the health industry delegates who attended expressed an interest in understanding what knowledge management might do for them. How might we do that?’.

Gada is one of those special people who when they pose a question you feel compelled to answer it. Which is why in a week’s time I am going to be back in Khartoum to participate in a two day Workshop on Knowledge Management for Health Care in Sudan.

Knowledge management in health is not new. The NHS Modernisation Agency was one of the early adopters and used a lot of Chris Collison’s thinking from Learning to Fly to build a pretty effective knowledge management operation with one of the first Chief Knowledge Officers in charge of it. Sudan’s health industry does not (yet) practice km in any formal manner so as part of the research for my presentation and the sessions I am facilitating I asked some of the actors in the NHS km story to reflect on more than a decade. Here’s what they said (names omitted):

I have said on several occasions that when you multiply the number of employees by the years of professional learning, the NHS is the world’s most knowledgeable organisation. Or it should be. With better networking, more curiosity, joined-up systems, a culture of improvement and leaders who value national above parochial, it would live up to its potential.

What I have seen is wonderful pockets of excellence – hospitals with a determination to improve, a passion for learning, and a curiosity which can even transfer lessons learned from Formula One pit teams to the operating theatres of children’s hospitals. Pockets of excellence indeed, but in threadbare trousers.

—————————————————————–

The idea of KM in that particular agency of the Department of Health was to ensure that the knowledge produced by one team (silo) would reach other teams (silos), that the whole organisation had a sense of who knew what, and that we could reuse knowledge across the Service.

We had a team of people and a CKO…a CoP with members from all different teams in the organisation; knowledge audit and SNA that involved quite a few people across the org and which changed the way they perceived the work of the KM team. Yet …our work became too focused on documents and content creation disguised as gathering of lessons learned.

——————————————————————-

In my regular interactions with physicians in the NHS, a key frustration has always been the flow of information between doctors and commissioners. Differing agendas, treating patients vs cost-effectiveness, cause breakdown in communication. The problem usually arises from the discrepancies between the notion of an ideal patient and the realities of people walking into the clinic. Pharma is not particularly helpful in addressing this through the research conducted, however the shift in emphasis to real world data by health technology bodies such as NICE is creating a cultural shift in the sector.

A great story of information exchange relates to a melanoma patient who was being treated in London. The patient was a successful business man so he continued with his work. He was treated with a very new drug and experienced severe side effects while on a business trip in Switzerland ending up at a hospital there. Mismanagement of this drug’s side-effects can result in death. The Swiss physicians had never used the drug before, and most were not even aware of its existence as it is a specialist therapy. However, there was extensive global information exchange driven by the company, which meant that as soon as they saw the patient card which all patients on the drug were advised to keep on their person, the Swiss physicians were able to access a database of information and a 24 hour network of world experts in the condition. Luckily for the patient the KM network worked thereby saving his life.

The shift towards greater use of data and increased use of technology (from other industries) is where I hope much of the Khartoum health discussion goes. One of the leaders in Health Information Systems shared this quote:

‘In the next ten years, medicine will be more affected by data science than biology.’

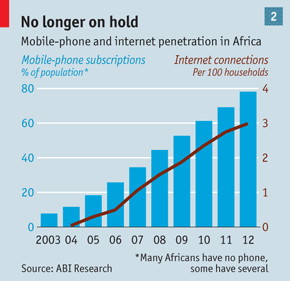

Today’s Economist article on the use of mobile technology in Africa is a timely reminder of the strides being made on that continent and how widespread adoption will present huge opportunities as well as challenges for the health industry there.

I am also going to share this clip from Grey’s Anatomy (US TV drama) about the use of Twitter in an operating theatre. Though fictitious it gives as good an illustration as any I’ve seen about the potential benefits of using mobile technology to share knowledge and mobilise a global community in the same was as the story of the melanoma patient above does.

As the F1 season is nearly upon us I was really struck by this clip from the BBC which shows how the Maclaren F1 Team’s driver and car monitoring system is being adapted/used in a children’s hospital in Birmingham.

And yet for the Sudan health system to adopt some of these technologies (against a backdrop of isolation) there has to be a huge mindshift. I recall with chilling clarity a phrase uttered by a health professional at KMCA Khartoum last year in response to a question I posed as to the barriers to the sharing of knowledge: ‘my information is my soul’.

In an environment where:

- sharing of information (let alone knowledge) can have serious consequences

- admitting a lack of current knowledge can cause a loss of face and prestige

- continuing medical education is not a core requirement for the right to practice

- the major drug companies have no presence and sell via distribution channels

- the physician is beyond reproach

we have our work cut out if we are to get positive outcomes from the event. Its an exciting prospect.