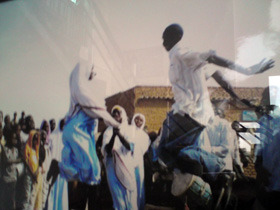

Meet Anwar, a Sudanese doctor. Just one of 5 fictional characters created by delegates at the Knowledge Management for Health in Sudan event I spoke at, helped plan and run.

This exercise, Scenarios for the future, was set in 2020 and invited the 80 or so delegates drawn from across the whole of the health industry in Sudan to consider what a day in the life of each character might look like. This was a new and warmly embraced concept in an environment where my information is my soul and much of the debate about the future takes place against a backdrop of uncertainty and increasing austerity where:

- 2/3rds of all drugs are purchased ‘out of pocket’ not from health system

- drugs are proportionately more expensive than in other domains

- funds from external sources are available to assist with health informatics.

Having settled on a description of each character the delegates who were by this time in groups of 8-10 then set about imagining what their day might look like on January 1st 2020. A vivid imagination is required and was evident in the quality of the stories that were told by each group’s nominated storyteller.

I will in due course and with the organising committee’s permission publish the two ‘winning’ stories; yes we did do voting while the storytellers left the room.

One of Sudan’s leading pharmacists noted in a one:one conversation how important listening was and how difficult a technique this is for many to use when prescribing drugs.

By inviting each of the storytellers to play back the story to each of the other groups it was good to hear them say in the summing up that by the end they really felt they were the character.

The previous day I’d invited the delegates to change the way they looked and think about issues and barriers. Using when you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change exercise conducted in the best breakout rooms I’ve ever worked with, the delegates who are naturally loquacious soon grasped the concept of seeing the room through the lens of different professions.

This change of mindset was important: it allowed the subsequent round table (well round conference room) session that discussed:

‘What are the biggest issues we face in sharing knowledge and information about the health of our nation and how can we overcome them’

I’d invited each delegate to introduce themselves to three people they didn’t know. This worked well and encouraged a very frank discussion. The main issues highlighted were:

- no systematic collection of information and limited understanding of its value

- transparency of process (where do the figures go) and credibility of the data

- lack of human resources to do the collection

- limited statistical information to undertake scientific research on

- ownership of data and the whole process – fragmentation

- accountability to deliver

- communication/awareness of what each organisation is doing – lots of ‘stuff’ is happening but there is a real risk of duplication of effort e.g. many of the disease control programmes are creating their own informatized information systems

Delegates recognised the tremendous strides being made by the Public Health Institute (one of the event’s sponsors and host of the official dinner) in developing professional public health administration programmes, the creation of a Data Dictionary and the publication of the first Annual Health Performance Review though many bemoaned the lack of official support for research projects where Sudan has a prominent global position, Mycetoma Research Centre an example.

I came away from reflecting on a discussion I had around the event:

Its all about ‘informization’ – the ability to report from a health centre level with ‘point of sale’ data collected via PDA’s / mobiles as well as computers; about logistics management as a result to ensure supplies get to where they can do the most use.

This can be monitored by the minister, routine reports can be prepared showing which centre reported, which district has complete reporting, which state has complete and timely reporting and % of stock outs of basic drugs or vaccines etc.

And inspired by many of the presentations I’d seen on the morning of the second day from University of Khartoum’s research centre and of course the Public Health Institute who are reaching out to try and create greater awareness through public forum, newsletter and other events.

Perhaps the presentation that struck the biggest chord was from EpiLab

who have achieved impressive results in helping to reduce the incidence of TB and Asthma and whose research and community communication techniques are highly innovative. I loved the cartoons they developed on how to self treat and prevent the incidence of illnesses which were drawn up BY the local communities. Their pictures and their words are published as guides for the nation and I know they will make them available so I can share them in future blogs.

It was an honour, a challenge but nevertheless great fun enhanced by the warmth of the welcome and a genuine sense of appreciation. Sudan’s people are among the most engaging and intelligent I’ve met. One anecdote from a conversation with a young professional in the communications business illustrates their dilemma:

‘…of the 95 people who graduated in my year a few years back 90 are now working overseas, the majority in highly paid good positions…’

In my address I acknowledged the support I’d had from many people in preparing for the event. They were: Ahmed Mohammed, Dr Alim Khan, Dr Anshu Banerjee, Ana Neves, Andrew Curry, Archana Shah, Chris Collison, David Gurteen, Dr Gada Kadoda, Dr Ehsanullah Tarin, Dr Madelyn Blair, Sofia Layton, Steven Uggowitzer, Victoria Ward